Complexities of a progress stepper in a checkout flow

When obtaining data from a customer during a checkout flow, stepper components have been a UX staple for a while already. Asking the user one thing at a time seems to generally help to reduce complexity and provides guidance through the flow. However, I’m not much of a UX guy, so that’s a topic for some other folks to talk about. What I’d like to talk about here are problems encountered while architecting and implementing them in the frontend. As I had to learn the hard way, there are quite a few things to trip over.

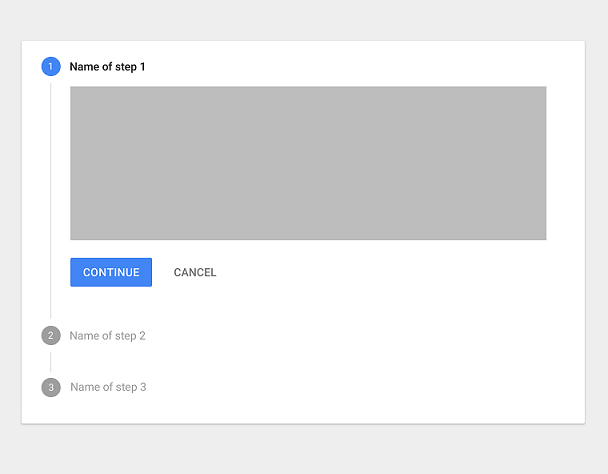

What a progress stepper looks like to the end-user (Material Design)

Are they really complex?

Well… yes and no. It really depends on your exact requirements. If, for example, the exact steps are already known in advance, are either completely static or require only very little dynamic support, then yes, they’re rather simple to implement.

However, there are plenty of scenarios and requirements that can make them fairly complex rather quickly:

- Dynamic steps: Depending on the users choices, the steps can change. Additional steps can be added or removed on the fly.

- Composability of steps: We might want to be able to easily compose new flows, reusing steps whenever possible.

- Browser history support: Especially on mobile, folks love to click the back-button. This should ideally not abort the entire flow. Keep in mind that persisting the “current step” in the URL will allow the user to jump to any of the previous steps at any point in time. We need to account for the possibility that jumping to that particular step is no longer valid. Furthermore, the user often navigates using a mix of all available navigation options, possibly leading to situations where “history.back()” is actually forward, from a stepper-point-of-view.

- Backend orchestration between steps: Before rendering a step, some data might have to be fetched. After a step, we might want to persist some data. The response we receive however might indicate that the steps need to change: E.g. we’re on the second step, once the user goes next, data is persisted and the backend will then (and only then) tell us what the next step is actually going to be.

These problems have to be addressed somehow - and ideally, especially on a bigger project, they’re addressed in a way that most developers working on the project won’t have to individually deal with these hassles. The principle of least astonishment is rather important here: If we implement an abstraction to make it easy to create such stepper flows, it should give some guarantees on how it behaves, and those guarantees should ideally match what one would intuitively expect.

Some Learnings

There are plenty of footguns while addressing the problems above, and I’ve made some learnings along the way.

Be ready for new requirements (and unexpected edge-cases)

The biggest and most important one is probably: Be open and ready for new requirements for your stepper. Unless it is set in stone that a flow won’t ever change and it is agreed with all stakeholders that we specifically implement just this exact flow and nothing else, prepare that sooner or later, there will be new requirements.

This sounds fairly obvious, but I’ve seen too many projects already (including some that I was part of) ending up in a tight spot because too many assumptions of what a stepper should and should not support were made early on, often to enable delivering some minimal viable product on a tight deadline that was a greatly simplified version of what should be possible later on. Another issue is that on the surface, it often really does look simple, so developers are tempted to just use some imperative coding without any abstraction. This often falls flat once we have to make things more dynamic due to tight, rigid coupling between the steps and the stepper.

Abstract towards declarative, configuration-based approaches

It can be very useful to abstract towards a declarative, configuration-based setup - because a configuration conveys the intent clearly. Even if the underlying implementation that executes based on the configuration changes, the original intent of the configuration is still clear. If we implement it imperatively, it can be hard to refactor it to be able to deal with new requirements. To give a bit of an idea, a configuration might look like this:

/**

* No matter the implementation, a config as below makes it clear

* that "some-flow" consists or step-A/B/C (whatever that might mean),

* and that we can expect them to appear in the listed order.

*/

const flowConfiguration: Record<flowIdentifier, stepIdentifier[]> = {

'some-flow': ['step-A', 'step-B', 'step-C'],

'some-other-flow': [

'step-A', // We might want to reuse steps across different flows.

'step-X',

'step-Y',

'step-Z'

]

};

/**

* Again: No matter how our implementation looks like and how much of it we need to refactor:

* It is clear that when "entering" step-A, we need to invoke "onEnterStepA",

* and when leaving it, we need to invoke "onLeaveStepA", and that whether

* step-A is shown at all, is determined by "isStepAShown".

*/

const stepConfiguration: Record<stepIdentifier, StepConfiguration> = {

'step-A': {

someLabel: 'Step A',

isShown: isStepAShown,

onEnter: onEnterStepA, // this could be an async function, a promise, an rxjs-subject, etc.

onLeave: onLeaveStepA

}

};

The primary motivation of such a configuration is really to decouple implementation from “declaration of intent”. This allows for much easier refactoring and implementation of new requirements.

You might wonder, why do we have some “onEnter/onLeave”-hooks directly on the configuration? Why not let the steps themselves handle whatever they need? When transitioning between the steps, we need to be able to give some temporal guarantees. For example, when we go from ‘step-A’ to ‘step-B’, ‘onLeave’ of ‘step-A’ must be finished before ‘onEnter’ of ‘step-B’ is started, as there might be a data-dependency. ‘step-B’ however should in no way be aware of ‘step-A’, hence, if we want to keep the steps independent, we need to find an abstraction which gives us these guarantees.

The configuration above is relatively simple - and fairly close to an early iteration I’ve once worked on. A few considerations:

- As per the above, the onEnter/onLeave operations have to be called in the correct order; they need to appropriately wait for each other as there might be a data-dependency.

- When going from ‘step-A’ to ‘step-B’, it could be a UX requirement that we show a transparent spinner on top of ‘step-A’, and only ever transition to ‘step-B’ when that step is entirely ready. Meaning: When we move away from ‘step-A’, we call ‘onLeave’, then we call ‘onEnter’ of ‘step-B’, and only once that is complete, we actually transition.

- During ‘onEnter’ of ‘step-B’, it could become clear that ‘step-B’ isn’t actually needed. If we need to support this case, we need to recursively trigger the ‘onEnter’ of the next step. We likely need to check for “isShown” multiple times to account for this scenario.

- It might be useful to have a “onSkip”-hook for a step. Meaning: If “isShown” says that the step isn’t needed, we might still want to trigger some step-specific calls which might be required regardless (the step not being shown is just a UI-thing, after all). This can help keeping a step “atomic”, meaning, we don’t have to take care of doing some calls elsewhere, which helps with keeping the steps composable. It will, however, increase complexity by quite a bit if we want to have temporal guarantees in which order these hooks are executed.

- The stepper needs to start somewhere. Usually the first visible step - but maybe for some requirement, someone wants to start at the second step, for whatever reason. Browser-history obviously won’t lead back to the first step but the user might still be able to navigate to that step via UI-interaction.

Do not fight the browser to enable browser history

If one of the requirements is to support browser history (meaning: history.back()/history.forward() behave as expected), one of my big

learnings is: Do not fight browser history. Embrace it. Even with all the odd cases you possibly need to think about, it’s still simpler than

trying to hack the browser to your will. Once a setup is in place, allowing for browser history to work as intuitively expected is quite

the magic to behold, it’s worth the effort.

A few concerns worth thinking about:

- Navigation-Direction matters. For example, we’re on step-2 and click the back-button - we’d like to navigate back to step-1. There’s some form however which is currently invalid. Navigation “back” to step-1 is arguably still valid. However, it “back”-navigation would lead to step-3 (e.g. because the user went back to step-2 by clicking in the UI, thus populating the history-stack with another entry), we’d need to block this navigation, as data on step-2 is invalid.

- “Forward-jumping” should at maximum allow one step forward (see below).

- From experience: It’s best (but not always okay with UX and other folks who might have a say how the URL looks like)

if the URL is agnostic to what step we’re currently on. Obviously, the URL needs to change between steps,

but detaching the URL from the step itself has quite a few benefits. My go-to-solution is a path-parameter like so:

step/3. The primary reason is that we don’t need to “correct” the URL: If we’re onstep/3, then go tostep/2, but there we change some data so thatstep/3is now a different one - if we click the back-button onstep/2, we can still go tostep/3, we just display a different step than it was before. If there’s a step-specific identifier in the URL, this needs to be corrected, which adds complexity. - When using a number: Do not consume it as an index in some array or some such, as this is a rigid coupling that will make a few requirements very hard to deal with.

For example, it can be a requirement to “drop” an earlier step after it was concluded. Makes mostly no sense, but sometimes it does, and in that case, if an earlier step is dropped,

it can be that a user is all of a sudden one step further than they should be due the tight coupling of the number in the URL. From my experience, it’s best to treat it only as a “delta”:

If a user goes from

step/1tostep/2, that means we go “+1” forward. If a user goes fromstep/5tostep/1, that means we go “-4” backwards. Allowing for steps to be dropped will also lead to some silly things like havingstep/-1in the URL possibly - if we only look at deltas, this can be fine (although still weird).

Allowing to jump forward more than one step is a trap

Imagine you’re the user on some step in a flow, but then realize that three steps earlier, you’d like to change something. We can simply click on the label of the corresponding step to jump back. Now, someone from UX might suggest or even require that if someone “edits” an earlier step, we can jump back to where we have originally been, skipping multiple steps in-between.

Unless flows are strictly static, allowing to “jump forward” is nothing short of opening pandora’s box. Some of the steps in-between could have changed due to dependencies to the earlier step, and either before or after jumping back we somehow need to account for this. It’s one of the very few requirements which I think is very ill-advised to implement. The dependencies between the steps aren’t always obvious, and on the surface, it can seem like an easy UX improvement, but allowing for arbitrary back-and-forth without accounting for all the dependencies in-between will open up edge-cases which will be very hard to control for.

Real users will go back and forth - tests should too

Supporting browser history and allowing to go back in the flow will introduce a lot of possible paths through the application. Real users will certainly make use of the back-button at any given point in time - the tests should also account for that! We tend to primarily test the happy path to go through the flow nicely one step after another - but our actual users will very much go back and forth. Having at least a few tests which specifically cover such scenarios is definitely valuable.

Conclusion

If the requirements demand for a highly dynamic progress stepper, it can be quite a tricky beast to tame, and it’s hard to build an architecture which takes care of all the edge-cases appropriately. Even after a few years of experience with such steppers, new surprises still occasionally surface - at least to me, it’s a rather interesting problem-space. Often, they look simple on the surface, and it’s therefore sometimes a bit of a struggle to make sure all the involved teams are on the same page. Ideally, for the devs involved, the setup “just works” (principle of least astonishment), but it can take a while to get there.